About Us

Our Team

Our Members

Our History

Our Values and Principles

What is Substance Use Health?

What is Safer Supply?

Land Acknowledgement

by millie schulz

About Us

Formerly known as the National Safer Supply Community of Practice, the Substance Use Health Network represents the next step in our shared journey toward health, dignity, and evidence-based support for people who use substances.

This evolving network brings together healthcare providers, harm reduction practitioners, researchers, peers, and advocates from across Canada—creating space for collaboration, knowledge exchange, and community-led innovation.

While our name has changed, our commitment remains the same: to support approaches that centre compassion, choice, and the well-being of individuals and communities.

The SUHN supports healthcare and social service providers as they provide a continuum of care options for people who use drugs at high risk of overdose and death. The SUHN serves as a resource for those who would benefit from learning about how to deliver care within a harm reduction framework in community health settings. However, this is not a teaching space - but rather a space where health and social care providers and people with living/lived experience exchange information, including clinical experiences, program operations, evidence, and personal experiences. Find out more about What We Do.

Our work is grounded in an anti-oppression and anti-racism framework and anchored on core values of respect, collaboration, equity, integrity, and curiosity.

Our Team

The SUHN is administered by Rebecca Penn, Project Manager. SUHN members work with Rebecca to develop documents, facilitate meetings, and organize events.

Our Members

Our interdisciplinary community of almost 2000 members includes healthcare providers, social care providers, advocates and activists, people who use(d) drugs, researchers, policy makers, and many others. For information about our membership, see Our Community. To see who are some of our organizational partners, visit Collaborating Organizations and Partners.

Collectively, we form a space where healthcare and social service providers and people who use(d) drugs exchange information including clinical experiences, program operational experiences, and personal experiences. Join us now!

Our History

SUHN began as the National Safer Supply Community of Practice (NSSCoP), which was formally launched in 2021 as a collaborative initiative between the London InterCommunity Health Centre, the Alliance for Healthier Communities, and the Canadian Association of People Who Use Drugs (CAPUD). It was created in response to Canada’s ongoing toxic, unregulated drug supply crisis and aimed to support the implementation of pilot safer supply projects funded by Health Canada’s Substance Use and Addictions Program (SUAP).

Between 2021 and 2024, with support from SUAP, the NSSCoP operated with a small but passionate team of three knowledge mobilizers. Together, they helped build and sustain a national community of practice by facilitating working groups, developing practical tools and resources, and organizing national knowledge-sharing events—including webinars, workshops, and symposia. The NSSCoP also hosted weekly interdisciplinary drop-ins, monthly program operator meetings, and clinical discussions, while offering a consultation service to support healthcare providers to prescribe safer supply as part of the care that they provide.

Throughout its work, the NSSCoP prioritized collaboration across disciplines and sectors, centering lived and living experience and fostering innovative, evidence-informed responses to drug use rooted in harm reduction. For more about the work of the NSSCoP, please see our 2024 Final Report: Celebrating the Magic of Community, Knowledge Exchange, and Solidarity-Building.

Now, as the needs of the community continue to evolve, the NSSCoP is expanding its scope and transitioning into the Substance Use Health Network. This broader initiative reflects a more integrated approach to substance use, encompassing not only the continuum of substance use care, but also the prevention, care, and treatment of sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections (STBBIs) and other related health concerns. The new network builds on the foundation laid by the NSSCoP, continuing to champion person-centered, evidence-based responses to substance use grounded in equity, dignity, respect for autonomy, and community leadership.

Our Values and Principles

Respect: We consider respect as fundamental for engaging in our community of practice. Respect is the feeling of regarding someone well for their qualities and traits, but respect is also the action of treating people with appreciation and dignity. We value all people and firmly believe each person deserves dignity, agency, and independence. This means honoring someone by demonstrating care, concern, or consideration for their needs and feelings. This includes being supportive, fostering people’s autonomy and freedom, and nurturing a community of practice built on solidarity, care, and compassion.

Collaboration: Our community of practice is built on interdisciplinary collaboration. Collaboration happens when people, groups, and/or organizations work together to achieve common, shared goals. Our interdisciplinary membership – physicians and physician assistants, nurse practitioners, nurses, people who use(d) drugs, harm reduction workers, researchers, program managers, policy analysts, and activists – come together to learn collectively from one another, build capacity and engage in skill-sharing opportunities, and develop shared practices. As a diverse membership, we uphold all sources of knowledge and value everyone’s individual expertise. Our collaborations also aim to be power aware by continually challenging the intricate power dynamics and imbalances that exist within and across groups. By working collaboratively, we can better share resources, coordinate key messaging, uplift each other’s work, build collective solidarity, and bolster community resistance.

Equity: We strive for equity in all facets of our community of practice. Equity means recognizing that we do not all start from the same place and that some people and groups disproportionately experience higher levels of oppression, trauma, stigma, and social and structural violence. We are committed to acknowledging this and making adjustments in our work and relationships to address these imbalances and injustices. We learn from an anti-colonial, anti-oppression, and anti-racism framework rooted in a spirit of reciprocity and prioritize social justice above all else. We aim to foster feelings of safety, belonging, support, and fairness for all community members holding diverse and intersecting identities, perspectives, and experiences. We equally work to ensure inclusivity, accessibility, and disability justice in our community of practice. This includes providing access to closed captioning and alternative text, publishing documents in various accessible formats, and developing user-friendly content.

Integrity: Integrity is a practice that includes being honest and showing a consistent commitment to strong moral and ethical principles and values. We know trust is earned and believe that the earnestness of our actions demonstrate our commitment to social justice, equity, and community accountability. This means we are accountable for our actions, take responsibility for our wrongdoings, find ways to remedy our errors, and maintain transparency in all of our work. We also acknowledge relationships are reciprocal and know we can strengthen our community by equitably sharing skills, exchanging resources, and offering mutual support.

Curiosity: Our community of practice thrives on the spirit of curiosity, generosity, progress, and positive change. Curiosity involves being open to exploration, investigation, learning, and critical thinking. By remaining curious, we nurture feelings of acceptance, normalcy, compassion, non-judgement, and understanding among our members. Questioning, analyzing, and challenging assumptions through our diverse perspectives and lenses helps us work towards transforming health care practices and policies to centre people who use drugs as leaders and experts in their own care. This means remaining committed to being compassionately inquisitive, asking difficult questions, sitting with and discussing discomforts, wrongdoings, and injustices, and navigating disagreements with openness, respect, and a desire to understand.

What is Substance Use Health?

What Is Substance Use Health?

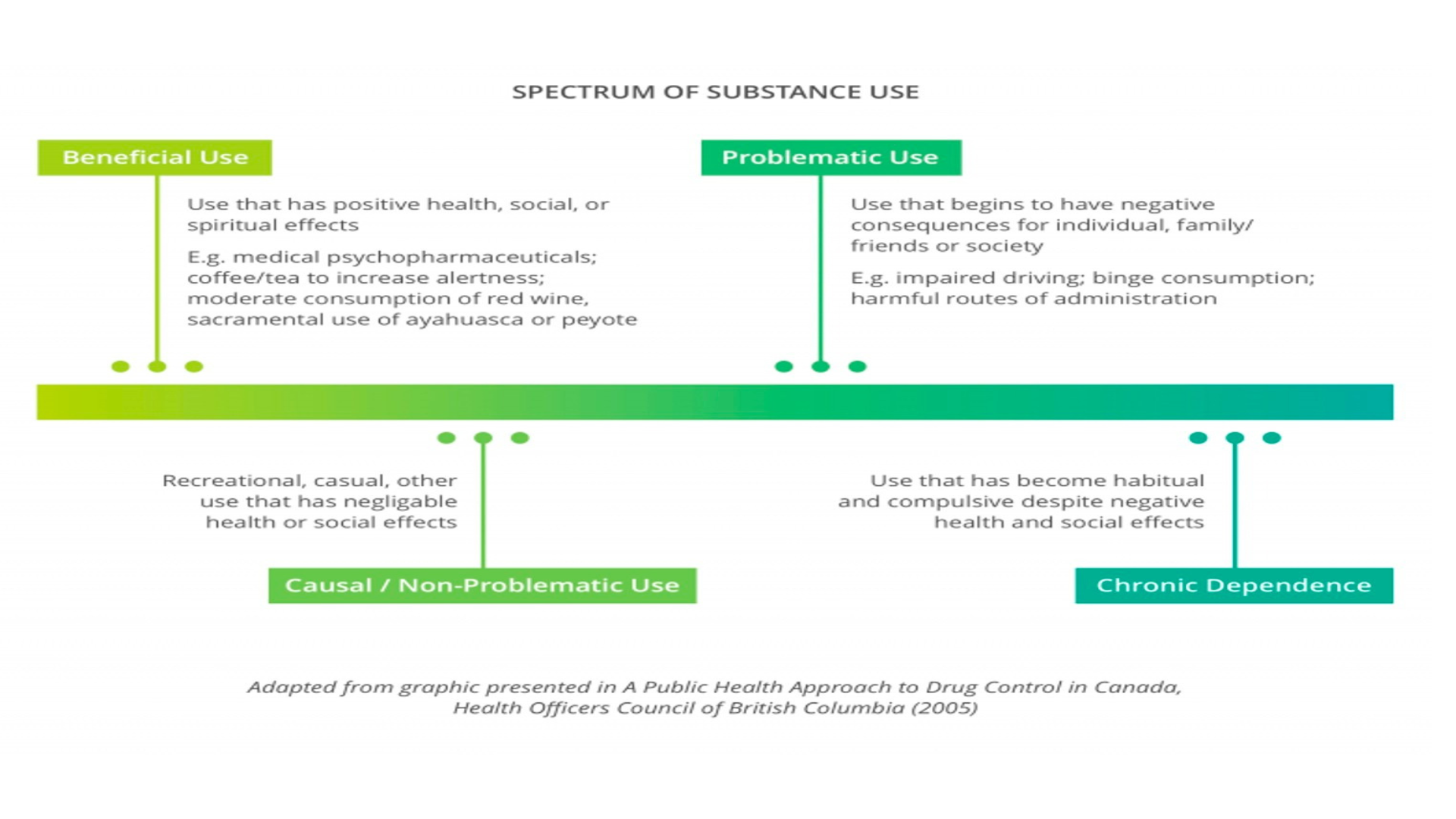

Substance use health is an emerging and inclusive term that broadens the conversation around alcohol and other drug use by recognizing it as a key aspect of a person’s overall well-being. Just as we speak of physical, mental, or emotional health, substance use health reflects the reality that people’s relationships with substances exist on a spectrum—from beneficial to potentially harmful. In this context, substance use is not automatically equated with illness or addiction, but rather is seen as one of many dimensions of human experience that can support or challenge personal wellness, depending on context and intention (CAPSA, 2022).

Like other aspects of health, a person’s substance use health can be positive—where substance use enhances their sense of well-being—or it can present challenges, often referred to as problematic use. This spectrum-based understanding helps shift the narrative away from stigmatizing or binary thinking (e.g., “user” vs. “non-user”) and toward a more compassionate, individualized view.

A Spectrum Approach to Substance Use

Substance use health recognizes that people use drugs for diverse reasons: to feel pleasure, manage pain, or cope with the demands of their environment. For instance, someone experiencing homelessness may use stimulants to stay alert and warm at night. A spectrum model acknowledges this diversity of use, ranging from non-problematic to harmful, and encourages care systems to respond accordingly (Carleton University, n.d.).

Health interventions within this framework include a wide range of strategies—harm reduction supplies, supervised consumption services, safer supply programs, opioid agonist therapy, and beyond. Equally important are structural and policy-level responses that address the social determinants of health, including barriers to housing, primary care, mental health services, and safety from violence, racism, and colonial legacies.

Substance Use Health Care: A Continuum of Support

Substance use health care operates along a continuum that integrates both psychosocial and pharmacological tools. On one end are traditional harm reduction services; on the other, clinical addiction treatments. What distinguishes this model is its flexibility and respect for personal agency. Individuals are not forced into a one-size-fits-all path but are supported to choose from a range of options that match their current needs and goals.

At the core of this approach are the values of self-determination, autonomy, and choice, underpinned by evidence that outcomes improve when people are empowered to direct their care. The goals of substance use health care include—but are not limited to—survival, basic needs, improved quality of life, mental and physical wellness, substance use stabilization, and connection to supportive services. These goals are deeply interwoven with broader systemic needs like:

Housing and food security

Access to health and mental health care

Safety from violence, racism, and colonial oppression

Income and education opportunities

Family unity and community belonging

Substance use health care is inclusive of all psychoactive substances—alcohol, opioids, stimulants, cannabis, and others—recognizing that many people engage in multi-substance use at different points in their lives. Care systems must remain adaptable, responsive to evolving scientific research, and rooted in lived experience. This “ecology of knowledge” ensures that evidence and experience are valued equally, and that programs remain grounded in equity, respect, and community empowerment.

Reframing the Harm Reduction–Treatment Divide

A foundational insight of substance use health is the integration of harm reduction and treatment rather than seeing them as oppositional. Harm reduction practices not only meet individuals where they are but also often serve as bridges to treatment when individuals are ready. As Kolla (2018) notes, “It is also important not to create an artificial distinction or opposition between harm reduction and treatment for substance use... the success of harm reduction programs at helping people who use drugs to access treatment has been documented.”

This unified model allows individuals to move fluidly along the continuum of care—whether their goals include abstinence, reduction, stabilization, or simply staying alive.

Citation for the Term Substance Use Health

The term substance use health was popularized by the Community Addictions Peer Support Association (CAPSA), which defines it as “a term to support the full range of positive and negative impacts associated with the use of substances,” with the goal of embedding substance use within a broader understanding of health rather than framing it solely through pathology or abstinence-based models (CAPSA, 2022).

CAPSA (2022). Substance Use Health. Retrieved from https://capsa.ca/substance-use-health

References

CAPSA. (2022). Substance Use Health. Community Addictions Peer Support Association. https://capsa.ca/substance-use-health

Carleton University. (n.d.). A Spectrum of Substance Use. [Institutional resource].

Kolla, G. (2018). Editorial: Integrating harm reduction and treatment.

What is Safer Supply?

Between 2016 and 2022, 36,442 people died from consuming unregulated drugs across Canada. In 2022 alone, 7,328 people died – a staggering rate of approximately 20 people dying each per day.

We can prevent the loss of people’s lives by changing drug policies that criminalize, stigmatize, and marginalize people who use drugs. We can prevent harms, including death, by ensuring that people have access to a safer supply of regulated drugs of known quality and potency.

Safer supply programs are an approach to addressing this ongoing health crisis by:

- providing a pharmaceutical grade medication as an alternative to the unpredictable and potent unregulated street supply

- working from a harm reduction approach that puts the needs and goals of people who use drugs at the forefront and improving access to non-stigmatizing healthcare and social services for people who use drugs

Prescribed safer supply reduces overdose risk and improves the health and wellness of people who use drugs.

The goals of safer supply are to:

- reduce people’s overdose risk and other harms arising from the unregulated street supply and the criminalization and stigmatization of drugs;

- increase people’s autonomy and control over their substance use; and,

- improve the health and wellness of people who use drugs.

Calls for a safe supply of drugs are not new, and people who use(d) drugs and healthcare professionals have been engaged in this work for decades now. Emerging evidence shows that prescribed safer supply saves lives and improves quality of life.

For more information about prescribed safer supply programs, please see Prescribed Safer Supply: Frequently Asked Questions.

Medical and Non-Medical Models of Safer Supply

There are different models for the provision of safer supply. A medical model makes use of regulated health professionals’ ability to prescribe pharmaceutical drugs within the context of a healthcare provider-client relationship. A medical model can be implemented in different ways, drawing on different approaches such as a “treatment” focus or a “harm reduction” focus. Current approaches include injectable opioid agonist treatment (iOAT; observed dosing); daily dispensed; and vending machines. For more information on safer supply models, please refer to Glegg et al., 2022.

The NSS-CoP focuses on a medicalized model of safer supply rooted in harm reduction because, in the current legal and regulatory context, it is possible to scale up quickly. Tensions between harm reduction and medicalized models create challenges, but together we strive to promote medical models that are people-centred, lower-barrier, and uphold people who use drugs as experts and that create space for them to be leaders and service providers. While a medical model fills a current gap on the continuum of care for people who use drugs, we know it is insufficient to meet the diverse needs of people who use drugs. We are committed to supporting policy change that enables the implementation of non-medical, community-led models of safer supply, as well as decriminalization, and regulation.

For more information about safer supply and its different models, please see CAPUD’s Safe Supply Concept Document, our Prescribed Safer Supply: Frequently Asked Questions document, our Emerging Evidence Brief on Prescribed Alternatives Programs, and additional Resources.

Why Safer and not Safe?

You may have noticed that we use the term “safer supply” as opposed to “safe supply”. There are several reasons for this positioning.

First, the term “safe supply” comes from the drug user movement. The current medicalized model does not reflect their vision of safe supply. The protocols and policies of current medicalized programs and the types of medications they provide do not adequately or appropriately address the diverse and expressed needs of people who use drugs. A medicalized model is only accessible to people who are diagnosed as having a substance use disorder, abandoning those who use substances recreationally or intermittently. Because medicalized models do not adequately address diverse needs, people who use drugs must rely on unregulated, toxic drug supplies, putting them at risk of drug-poisoning and overdose and death. Ultimately, “safe” supply as outlined by the drug user movement, has yet to be legally realized. For more information about their concept of safe supply, please see CAPUD’s Safe Supply Concept Document.

Additionally, Health Canada and medicalized programs use the term “safer supply” to acknowledge that the use of opioids (and medications in general) always comes with some risks and so cannot be called “safe”. However, “safer” works to acknowledge that a drug of known quality, composition, and potency is less risky than drugs purchased on the street from an unregulated market.

Guiding Principles for Providing Safer Supply

We endorse the guiding principles for providing safer supply that are presented in the guiding document: Safer Opioid Supply Programs (SOS): A Harm Reduction Informed Guiding Document for Primary Care Teams (Hales et al., 2020). These principles are:

People who use drugs are experts

People who use drugs are knowledgeable about the culture of drug use and their own goals and needs. Collaborating with people who use drugs is critical to developing successful programs and strategies to address the ongoing unregulated drug toxicity crisis. Their expertise should guide the development, implementation, and evaluation of all safer supply programs.

Participant-led and participant-centred care delivery

Programs will aim to support people to meet their current goals for drug use in the safest way possible. The aim is to provide compassionate and equitable health care to all people who use drugs.

Harm reduction

Programs will recognize that drug-related harms stem from several different sources, primarily from the criminalization of people who use, share, and sell drugs. Programs aim to reduce some of the harms associated with drug use by providing a regulated, safer drug supply. Clinicians will respect people’s autonomy, agency, and choices around drug use and accessing healthcare.

Lower-barrier care

Programs will be as accessible as possible. Clinicians will strive to meet participant needs and ensure access to a continuum of care through flexibility, problem solving, and collaboration.

Non-punitive approach

Missed doses or assessments or continued use of the unregulated drug supply will be addressed with compassion through dialogue and support and will not result in discharge from the program.

Land Acknowledgement

We come together in this community of practice from across Turtle Island, as people who live on treaty lands and ceded and unceded territories. We are all treaty people.

Our team is comprised of individuals and organizations from across Turtle Island, including the traditional lands of the Anishinaabek, Haudenosaunee, Lūnaapéewak and Attawandaron, on lands connected with the London Township and Sombra Treaties of 1796 and the Dish with One Spoon Covenant Wampum (London); the territories of the Mississaugas of the Credit, Anishnabeg, the Chippewa, Haudenosaunee and Wendat peoples, covered by Treaty 13 signed with the Mississaugas of the Credit and the Williams Treaties, signed with multiple Mississaugas and Chippewa bands (Toronto); on the lands covered by Treaties 16 and 18, which are territories of the Huron-Wendat, Haudenosaunee, and Anishinaabeg peoples (Barrie); in Alderville, home to the Mississauga Anishinabeg of the Ojibway Nation; in Tiohtià:ke (Montréal), which is located on the unceded territories of the Kanien’kehá:ka Nation; and in Ponamogoatitjg and Sogumkeagum (Dartmouth and Shelburne, Nova Scotia), the traditional and ongoing lands of the Mi’kmaq.

We work in a sector whose goal is to address social and structural harms. We recognize that the production of these harms comes from our colonial history and its enduring practices, institutions, and ways of thinking in our ongoing daily lives. We know that Indigenous people, as well as members of the African, Caribbean, and Black communities, are disproportionately harmed and criminalized by drug policies that are rooted in racism and colonialism.

Colonialism is with us today, and we commit to working in ways that transform racist and colonial institutions and practices, to repair harms, prevent future harms, and to work towards a more inclusive and equitable future.